Norumbega, New England’s lost city of riches and Vikings

“Here, at modern Watertown, was the ancient CITY OF NORUMBEGA.”

While preparing data for another spare time local interest map (forthcoming), I ran across a tiny bit of information (“Horsford’s Norse exploration theory”) that ended up captivating me for the weekend. It is the story of Norumbega, at various points a regional name applied to New England, a legendary city of riches, and thanks to a baking powder magnate, an 11th-century Viking city established by Leif Erikson in the modern-day Boston area.

Now, having been aware of this for no more than two days, and knowing little about historical cartography, I won’t claim any expertise or even to have all my facts straight, but let me summarize as best as I can.

In the 16th Century, not long after the European “discovery” of the Americas, Norumbega (with varied spellings and an uncertain etymology) began to appear on maps as the name for roughly what is now New England. It would come to refer to a region, a river, and a city, variously. As a city, it was apparently from the beginning legend—a place that was said to exist (no doubt along with other cities) but which had not been located. More than that, it came to be a downright mythical place, a city of endless riches—something like a northern El Dorado. The story of David Ingram, a shipwrecked English sailor who trekked all the way from the Gulf of Mexico to New England, made the rounds:

He saw kings decorated with rubies six inches long; and they were borne on chairs of silver and crystal, adorned with precious stones. He saw pearls as common as pebbles, and the natives were laden down by their ornaments of gold and silver. The city of Bega was three-quarters of a mile long and had many streets wider than those of London. Some houses had massive pillars of crystal and silver

Somehow Norumbega became associated more specifically with the Penobscot River in present-day Maine, with the city being around where Bangor is now. Samuel de Champlain explored the area in 1605, apparently looking for the city, but found no evidence of civilization. It seems that this quieted the myths of Norumbega’s fabulous wealth. But the name didn’t disappear and will still be encountered today in that area.

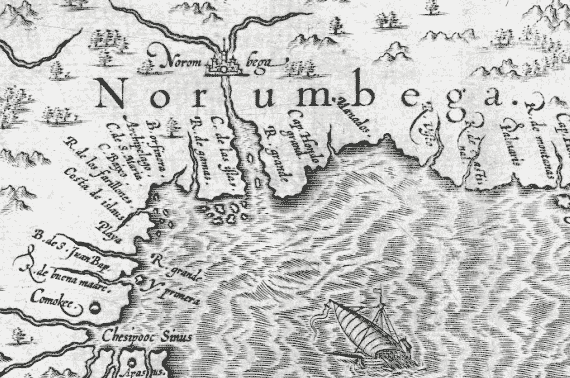

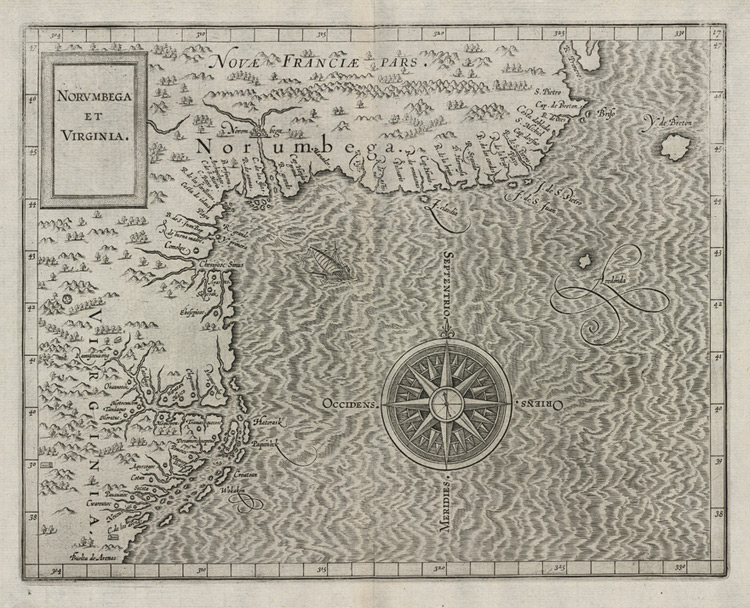

Many maps show the Norumbega region, and I can’t hope to do justice to that cartographic history, but Cornelius Wytfliet’s 1597 map, shown in detail at the top of this post and in full below (see a zoomable high-res version here) is a good example, and its Norumbega does bear some resemblance to the Penobscot River and Bangor.

Let’s fast-forward about 270 years to the dealings of high society in Boston, for the twist that makes Norumbega different from typical cartographic legend. In the 1870s a committee formed to back the erection of a statue of Leif Erikson, the famous Norse explorer. Proposing this was the renowned Norwegian violinist Ole Bull, with support from some others like the prominent American poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. Although proof would not be uncovered for another ninety years in Newfoundland, by this time the theory of Viking discovery of North America was somewhat popular. Furthermore some people had a notion that this Viking settlement had occurred in New England, i.e., that Vinland was or included New England. Gloria Polizzotti Greis of the Needham (Massachusetts) Historical Society explains why the idea of Norse discovery had traction with the Protestant elite of Boston:

So, Boston’s elite in their well-heeled gathering places, began to identify themselves with, of all people, Leif Eriksson. Why? Because of Christopher Columbus.

Columbus personified the growing political and social power of Boston’s Catholic immigrants. Even though the Irish and Italians maintained distinct communities themselves, to the old-line Protestant establishment they represented a significant threat to the status quo.

[…]

For the Protestant elite of Boston then, Leif Eriksson was the anti-Columbus. They saw him as fair and Nordic, where Columbus was Italian; Columbus brought (as they thought) superstition and slavery to the New World, Leif brought progress and commerce; if the possibility had existed in his day, Leif was the kind of man who would certainly have been, well – Protestant, like them.

Anyway, as time wore on, and as backers like Longfellow died, there emerged a Leif Erikson champion in Eben Horsford, a chemist and Science professor at Harvard. Horsford was best known for his formulation of baking powder but was also a strong proponent of the New England-as-Vinland theory in his spare time. Beyond that, he was convinced that the legendary Norumbega was actually Vinland. Using his baking powder fortune, he devoted much effort to uncovering evidence.

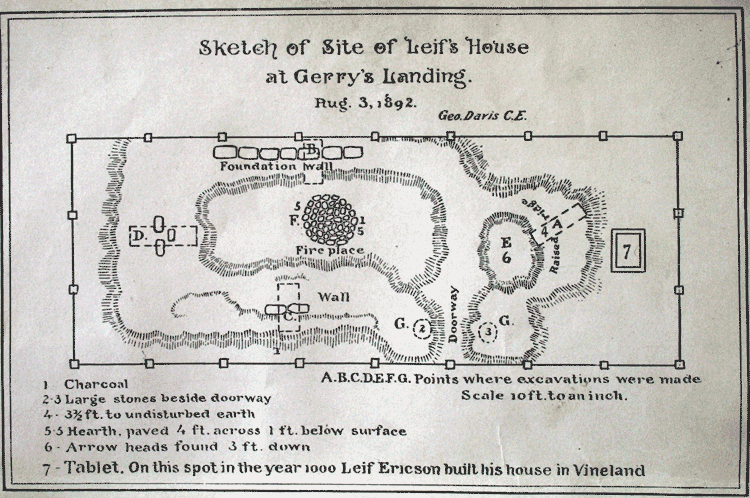

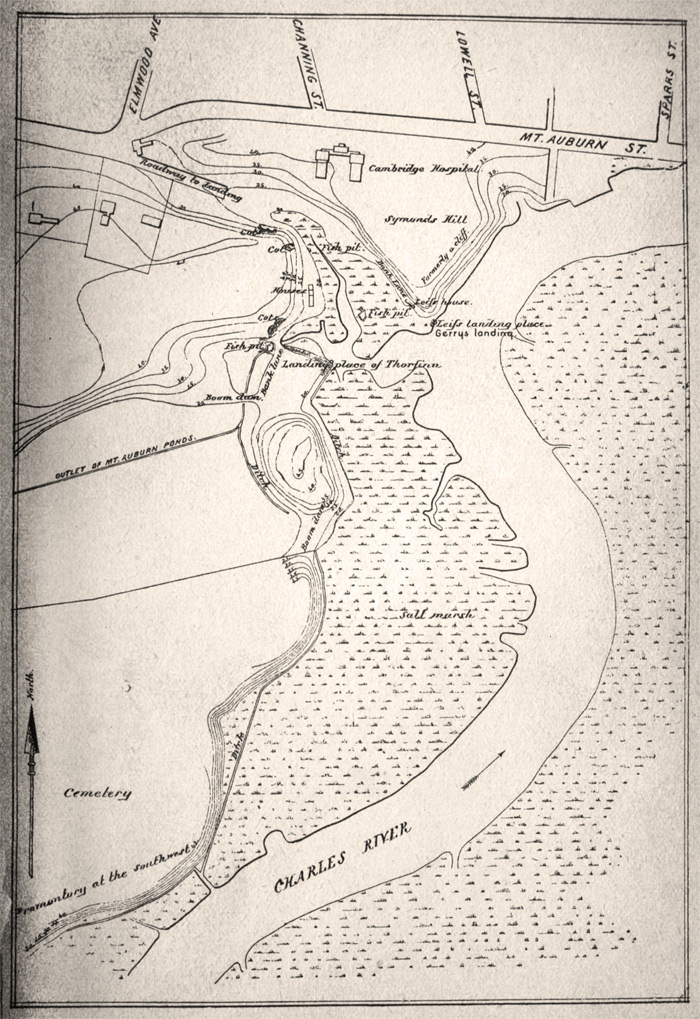

By 1890 or so, after a bit of digging near his home in Cambridge, Massachusetts, Horsford claimed to have found the site of Leif Erikson’s house at Gerry’s Landing on the Charles River near what is now Mt. Auburn Hospital (which is the last known site of my appendix, by the way). There he placed a plaque that remains today. Then he proclaimed that he had discovered a Viking settlement and the famous Norumbega itself farther west on the Charles River. He had a stone tower built to commemorate his first discoveries at the confluence of the Charles and Stony Brook in Weston, across from the soon-to-be-established Norumbega Park in Newton; the city of Norumbega was, as my opening quotation says, downstream at modern Watertown.

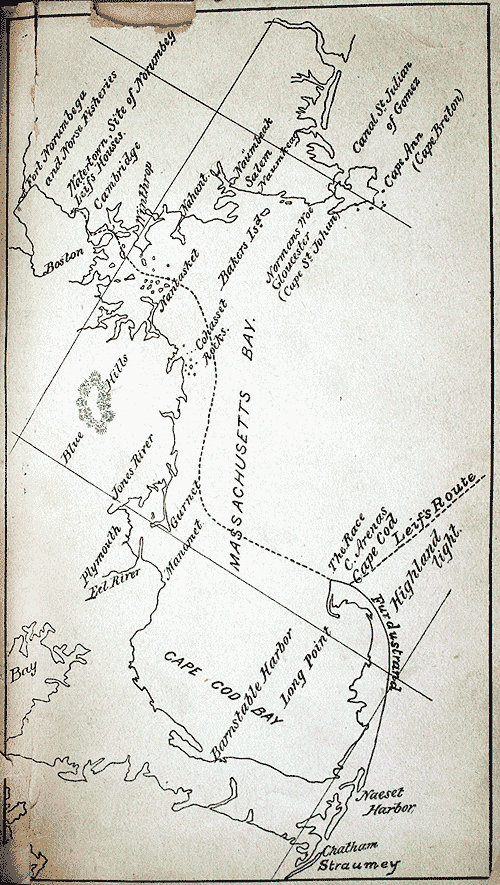

Leif, it seems, had hit Cape Cod and then entered Massachusetts Bay, sailing into Boston Harbor and up the Charles. The disastrously difficult-to-read map below (some shading to distinguish land from water, please!), from A guide-book to Norumbega, shows Leif’s route as the dashed line. In the upper left are indicated some of Horsford’s Norumbega sites. This book, written in 1893 by Elizabeth Shepard, directs visitors to Horsford’s supposed archaeological sites (even providing some directions via streetcar) while placing them within the context of the Icelandic sagas that tell of Vinland.

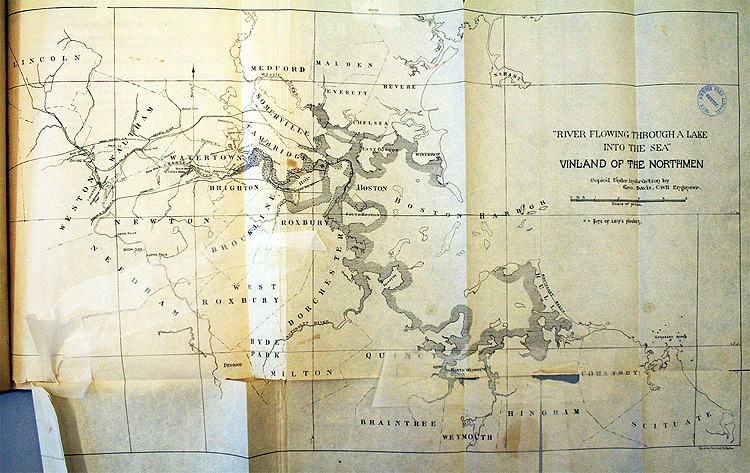

Another map shows the landing site of the Norsemen in present-day Cambridge. See also its location on a modern map.

Professor Horsford himself had of course published his discoveries, first briefly in The Discovery of the Ancient City of Norumbega and then with more detail in The Defences of Norumbega (among a number of works on the subject). Both of them include the Charles-as-Norumbega map below. I’m not entirely certain what the coastal shading indicates, but it seems to show the coastal area in Leif’s time. (Click the image to enlarge.)

Here’s a detail showing the sites—trenches, dams, etc.—along the Charles. Clicky for an expanded view. Three streets in western Cambridge—Norman, Norumbega, and Thingvalla Streets—commemorate Horsford’s theory and were laid out around the turn of the century at the Amphitheatre (one of the Norse sites) marked on this map just above the second W in Watertown.

The Leif Erikson statue was erected in 1887 and now stands (with a decidedly classical, non-barbaric appearance) as the westernmost of many statues lining Commonwealth Avenue in Boston. Although the Vinland theory that Horsford advocated enjoyed some popular support at the time, his claims have been dismissed for the lack of convincing evidence, not that he didn’t try to provide any. Nevertheless, in some local names and landmarks is preserved the idea that not only was legendary Norumbega a real place, it was a inhabited by people who sailed across the Atlantic some one thousand years ago.

Sources and further reading

- My two block quotes and much of the overview here comes from Gloria Greis’s fascinating article on the subject. It is probably the best source for learning this whole story.

- Professor Horsford’s report, available on Google Books, provides the opening quotation in this post and some additional information, but I only skimmed it and the subsequent Defences of Norumbega, instead trusting secondary sources like the one above.

- Elizabeth Shepard’s A guide-book to Norumbega and Vineland: or, The archæological treasures along Charles River is a nice summary and interesting approach to Horsford’s sites, and is also a fairly concise recap of how these mesh with the Icelandic sagas.

- The maps from Shepard’s and Horsford’s books are presented here as photographs, as you can tell. Those from the latter are poorly reproduced (if at all) in the digitized version on Goolge Books, so in both cases I consulted local libraries and brought a camera. Very few of the pages in Shepard’s book remain bound in the copy at the Boston Public Library, but at least they were all still present!

- Horsford’s address at the statue’s unveiling is also on Google Books. I’m not sure if it mentions his “discoveries” on the Charles, as it predates the other works, but I didn’t easily find references to it. It’s also dreadfully long, and I’m glad I wasn’t there to hear him.

- A second-hand account of Horsford’s work, and some cartographic history of Norumbega (though sans images), is provided by Rasmus B. Anderson in a chapter the 1906 book The Norsemen in America.

- I did little more than fan the pages of an edited volume called American Beginnings: Exploration, Culture, and Cartography in the Land of Norumbega, but it contains much more detailed history (cartographic and otherwise) of the region.

- Norumbega Reconsidered (PDF) is yet another work I didn’t really take time to read, but there is a section called “The Myths of Norumbega” that nicely summarizes the various things that Norumbega has meant.

Tagged Boston, cartography myth, history, vikings

13 Comments